Write a prompt, ask a question, and some generative AI app will spit out a conglomeration of all of the knowledge in the world (well, or at least the knowledge recorded publicly on the internet before 2020) and boom: instant knowle1dge work replacement.

Students are already using programs like ChatGPT to write essays, technologists are heralding a work future where you never have to do anything hard or boring again (or even better, where you never have to interact with a human, especially not one you find unattractive), and those of us who make money using our knowledge are a little worried.

If Github Copilot is already making coding easier and letting people build programs beyond their skill level, and ChatGPT is replacing the reasoning process for simple ideas by spitting out key points and outlines, and DALL·E is giving everyone on the internet the opportunity to make fantastical graphics with only a few keyboard strokes, what does that foretell for the future of knowledge work?

Making Emails For A Living

Knowledge work is a term that was coined by famed management consultant Peter Drucker in the 1950s, and is used to describe labor that depends on cognitive, rather than manual, work. It’s a somewhat fallacious classification, since most manual work requires immense cognitive skill and knowledge, but the distinction is most clear when we look at the product: do you make physical objects, or do you make emails?

If you have an email job, or any job where your primary product is information, or you make courses, or you coach, or you code, or you provide services that depend on your brain more than your brawn, or your run an online business that does not have a UPS account, you may be a knowledge worker. Creatives often fit in this category, too, especially if they are media workers. What all of these jobs have in common is a dependence on communicating knowledge to create value that can be monetized. Language is the center of knowledge work, and it is not surprising then that generative AI, which is based on natural language processing and depends on written prompts to produce a result, makes it feel like knowledge work is under attack.

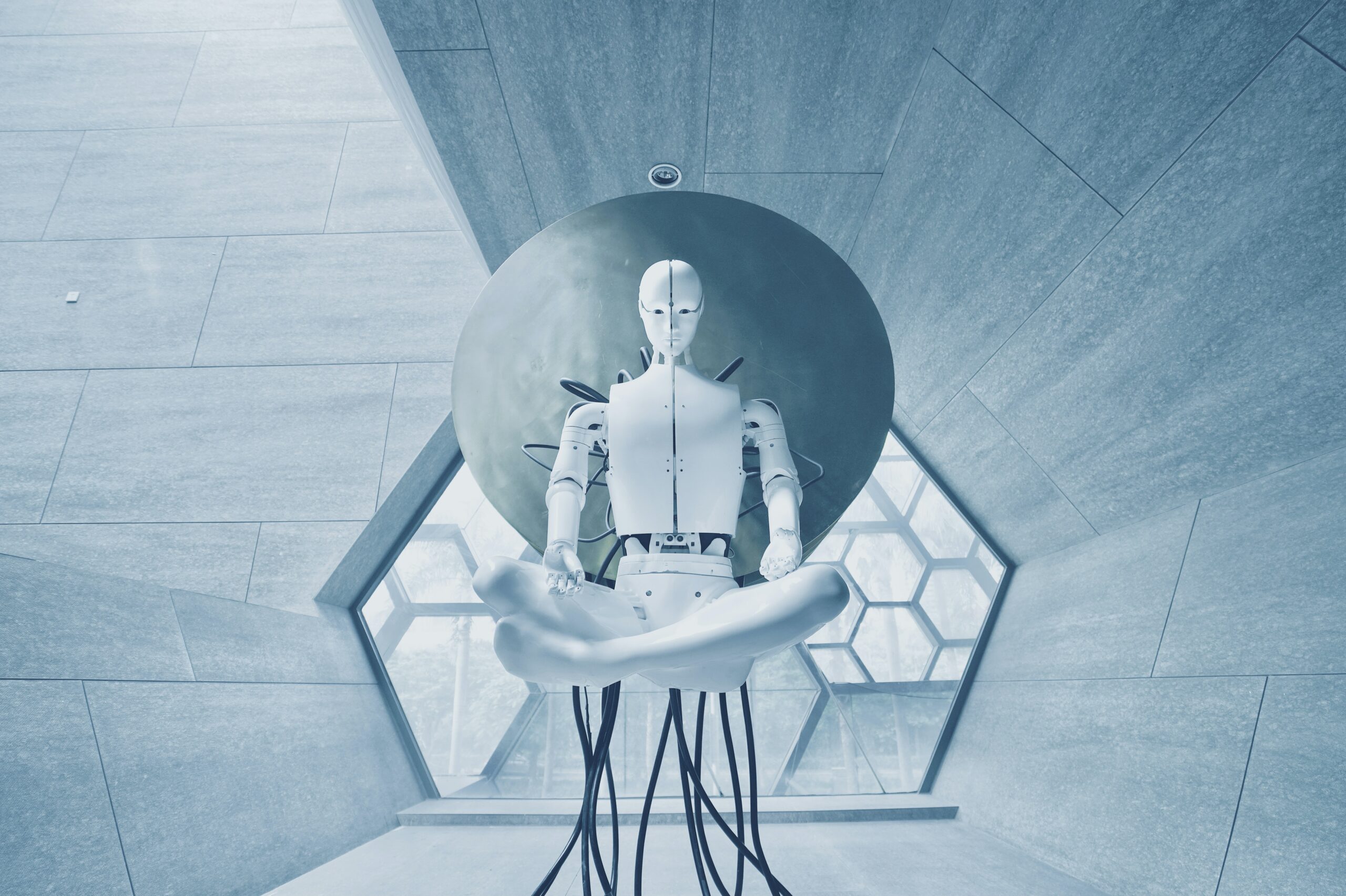

But generative AI is not the death knell of knowledge work, despite plenty of discourse to the contrary. That’s not to say that knowledge work is safe, though. It is certainly dying. Generative AI is a symptom, a manifestation of a rot writ large in our imaginations, the magnificent and terrible monster that mirrors the deeper fear. Our response to it is pointing to something more profound: the existential crisis of work itself.

The Crisis Of Work

The state of work in 2023 is not a pleasant scene. Mass layoffs in tech feel retaliatory against a strong labor market, union busting is practically a national pastime in the United States, and Jerome Powell at the Federal Reserve is saying the quiet part out loud: more people in the U.S. need to lose their jobs for inflation to go down, never mind that price increases are driving record profits. (There is a fundamental flaw with an economic system that requires unemployment, as well as with one that conflates corporate price gouging with inflation.)

And in the midst of it all, AI. Or what purports to be AI. A black box remixing copyrighted works and threatening your job!

Why does it feel like such a threat, when the best ChatGPT can do is write at a third grade level and get most of its facts wrong, and the image generator fingers—oh the fingers—are so disturbing?

While Generative AI has massive ethical issues1, it’s really kind of boring and not yet all that useful. Being able to make 100 avatars with a few swipes is not a sustaining magic. Asking a chatbot for information is a direct AskJeeves callback, internet search but make it conversational and even less accurate. And the pervasive idea that AI is inevitable is a particularly egregious sleight-of-hand that allows its creators to absolve themselves of responsibility for making these tools in a kind of reply-guy “just asking questions” entrepreneurship that Silicon Valley loves.

But the threat—the fear that our jobs will go away—hits at two core truths: basic stability does not exist even in a time of extreme wealth in extremely wealthy countries, and the work we do is so meaningless that a faulty computer algorithm can replace us.

That’s right. Many of us are doing deeply meaningless work, and we know it.

Enjoying this essay? Subscribe to Think Piece for more deep thinks direct to your inbox 👆

Knowledge work has been severed from anything resembling aliveness, codified into a series of processes, and turned into a mechanized product. Instead of using automation and yes, even AI, to minimize drudgery, we’re limiting the thinking power of knowledge workers, acting directly counter to the curiosity that is at the heart of creating. What was once focused on growing knowledge is now dependent on reformatting knowledge; we move widgets rather than building worlds.

The mechanization of knowledge work is following the well-honed model of scientific management created by Fredrick W. Taylor in the early 20th century, and the related Fordism that perfected the hyper-specialized assembly line. These outgrowths of the industrial revolution stain modern work, with everything from Standard Operating Procedures to the very idea of productivity emerging from a factory model of work.2

Generative AI is the next step in that legacy, and even though optimists think it will help knowledge work to be better and faster, it’s just another algorithm flattening creativity by regurgitating existing information without nuance or analysis.3

It has been relatively easy to homogenize knowledge work because we’ve already changed the frame: these are no longer creative pursuits, but rather jobs of reformatting existing knowledge to meet algorithmic demands. Moving knowledge around is disembodied work. It is not generative; it is transposing rather than transforming. Which is literally what GPT-3 enables something like ChatGPT to do.

Can Knowledge Work(ers) Survive?

In order for knowledge work to survive—and with it any hint of respect for the necessity of thought in the development of a better world—we must make work that can’t be done solely by a machine. We need personality-driven, weird, niche work. We need what Kyle Chayka is calling an artisanal internet, and I’d venture, an artisanal economy, where humanity adds the value, rather than creating value by removing humans.

As knowledge workers, whether we’re building software or creating courses, writing essays or curating ideas, documenting processes or moving data around, we must create a new space for thought, where knowledge is understood to be more than facts, and where experience provides value that no computer can mimic or comprehend.

Artists have much to teach about this space, this wedge into the flow of time that with our cultural and political contempt of art has to be forced on a continuous basis. Alexander Chee, in the final essay of his book How To Write An Autobiographical Novel, wrestles with the purpose of writing at all in the face of the personal and collective tragedies he’s experienced in his life. He walks the reader through the 2016 election, the AIDS crisis and those he lost to government neglect, 9/11, and other terrors that dim the light of possibility and make any generative work feel insipid and narcissistic. Throughout the essay, Chee asks, “What is the point?”

He finally answers:

The point of it is in the possibility of being read by someone who could read it. Who could be changed, out past your imagination’s limits. Hannah Arendt has a definition of freedom as being the freedom to imagine that which you cannot yet imagine. The freedom to imagine that as yet unimaginable work in front of others, moving them to still more action you can’t imagine, that is the point of writing, to me. You may think it is humility to imagine your work doesn’t matter. It isn’t. Much the way you don’t know what a writer will go on to write, you don’t know what a reader, having read you, will do.

Knowledge workers have adopted this outlook, that our work doesn’t matter, and that’s why it’s so easy to see AI as the monster: we’ve let this happen. We’ve allowed the productization of our thoughts, focusing on what is palatable rather than transformational.

Yes, we’ve had to survive, the non-existent social safety net pushing everyone who isn’t truly wealthy to do whatever it takes to maintain the lifestyle that is culturally required for your class, let alone simply pay the bills.4 Chee writes beautifully about this in the essay, too, honing in on the inherent class instability and even betrayal required to do creative work in the absence of sustainable access healthcare and housing.

Transformation Beats Palatability

But the funny thing is, as anyone who is any good at sales knows, transformation is more effective than palatability to drive revenue any day. Good work, with a focus on facilitating change and opening the possibility to Arendt’s freedom to imagine what you cannot yet imagine: that is actually what sells. At this fulcrum where knowledge work is on its deathbed and the threat of its replacement by generative AI is real because of the insipid nature of our products, we can actually align creative knowledge work and good business.

And unlike the dominant tech narratives, we don’t have to just find ways to do things faster, or marginally better, or to invent problems that don’t exist in order to sell new things. We need to envision the effect of our work on that one person, those thousands of people, who will do something that we can’t imagine because they engaged with our knowledge.

It is going to require a self-trust that I am afraid most knowledge workers and creators have lost. We will need to trust intuition over algorithmic hacks. We’ll need to prioritize our ability to experience the world and synthesize that experience rather than co-opting the experience of someone else in order to go viral. We’ll also need to remember that, despite tech’s efforts to professionalize and neuter knowledge work through mechanization, thought is inherently creative, and will likely require some kind of betrayal of social mores in order to thrive.

AI can replace your job because your job right now is meaningless. What will you do to make it transformational? To put the thought back into knowledge work? To let the fingerprints of your experience open the doors to possibility for others? To question deeply the assumptions of those creating the future, and offer alternatives?

Let’s do that work.

Special thanks to Fadeke Adegbuyi and Rachel Jepsen for early feedback on this idea and for pointing me in the direction of that insane Balaji thread.

It’s often factually incorrect, it was built on copyrighted works without compensation, human bias is extremely evident in what it produces, and it uses huge amounts of energy…↩

To be clear, I love an SOP. So practical. Much time saved. But it is part of the overarching problem of knowledge optimization, and needs to be named as such.↩

I could go down a rabbit hole on the potential of automation to create a post-work world, and maybe I will in another essay. But so far, that hasn’t happened: the dramatic increases in human productivity resulting from Taylor et al in the 20th century only led to more work and to more people doing that work, because we have an economic system that requires perpetual growth and cannot possibly give time back to workers.↩

I’m not a simp for the rich, but it’s worth reading this New Yorker article about the Getty family trusts, and then The Cut’s article about the Fleishman effect and the anxiety of upper class mothers in New York City; there’s a difference between being wealthy and being rich that is tied primarily to whether or not you need to work. The wealthy do not.↩